Trude Fleischmann (1895-1990) est l’une des grandes photographes du 20e Siècle. Elle était une de ces jeunes photographes juives confiantes, qui ont fait une carrière traditionnelle dans une profession masculine. Elle a photographié les étoiles du théâtre, des danseurs et des intellectuels. Trude a développé une passion pour la photographie dès son enfance, et est rapidement devenue l’un des plus grands photographes de portrait de Vienne peu après l’ouverture de son propre studio à l’âge de vingt-cinq ans. Même si elle est largement méconnue aujourd’hui, ses portraits d’intellectuels et d’artistes, y compris Karl Kraus (1874-1936), Peter Altenberg (1859-1919), Adolf Loos (1870-1933), Alfred Polgar (1873-1955), Stefan Zweig (1881-1942), Alban Berg (1885-1935), Bruno Walter (1876-1962), Max Reinhardt (1873-1943), Paula Wessely (1907-2000) et Grete Wiesenthal (1885-1970), reste un témoignage important de la culture européenne du XXe siècle

Issue d’une famille aisée, elle peut recevoir le soutien financier nécessaire dans son début de carrière. Sa formation comprend un semestre à étudier l’histoire de l’art à Paris et trois ans au « Lehr-und Versuchsanstalt für Photographie und Reproduktionsverfahren, » où les femmes avaient été autorisés à étudier la photographie depuis 1908. Après avoir terminé ses études en Juillet 1916, elle est devenue apprentie photo-finition dans l’atelier de la portraitiste bien connue madame d’ora (Dora Kallmus et son mari…. ), dont le travail qu’elle admirait. Parce que d’Ora se plaint de sa lenteur, Trude quitte sa place après seulement deux semaines !!!! . Mais elle rebondie très vite car peu de temps après, Trude trouve une place auprès du photographe Hermann Schieberth, dont les clients de la scène culturelle et intellectuelle viennoise étaient très friands. En 1919, elle devient membre de la Société Photographique de Vienne. ( Les plus célèbres d’entre eux comprennent – aux côtés de Trude Fleischmann – Edith Barakovich, Grete Kolliner, Marianne Bergler, Pepa Feldscharek, Hella Katz, Steffi Brandl, Kitty Hoffman, Edith Glogau, Trude Geiringer et Dora Horowitz).

Après trois ans, et avec l’encouragement de sa mère et le soutien financier de sa famille, elle a fondé son propre studio en 1920. Elle a pu poursuivre une carrière réussie entre les deux guerres car elle réalises des photos de mariages ou de baptêmes, et qu’elle reste sous contrat avec des magazines. Le « boom » de la photographie à cette période , lié à la croissance des magazines féminins ou non d’ailleurs , a également contribué à sa carrière.( par exemple Die Bühne, Moderne Welt, und Mode Welt et Uhu, en autriche, mais elle contribue aussi à la presse internationale) Elle réalise des portraits artistiques des célébrité du monde des arts ( l’opéra (chefs d’orchestre et chanteurs) , la musique, la danse et de théâtre) mais également des portrait de grands scientifiques, de politiciens et de professionnels de la photographie . Ainsi, elle devient rapidement indispensable à la presse autrichienne et internationale.

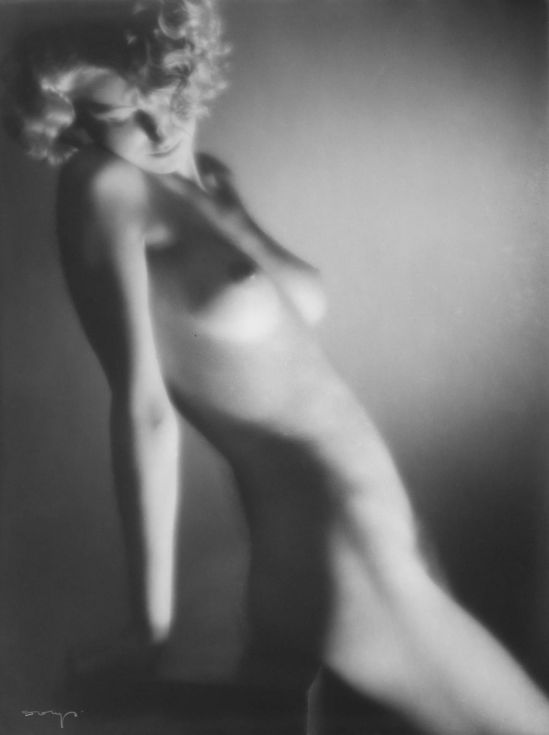

Comme son cercle d’amis dans le monde de l’art a grandi, le studio de Fleischmann est devenu un lieu de rassemblement pour l’élite culturelle de Vienne. Son manque d’assignations fixes et les clients lui a permis plus de liberté dans ses choix de thématiques et son style. Elle a une façon bien particulière de fixer l’expression des visages, et un regard érotiques sur les corps de ses sujets qui lui ai propre. L‘esthétique de Fleischmann a ouvert une nouvelle ère: Elle a appelé à la présentation d’une « nudité naturelle », et elle s’efforçait de ne pas « ajouter » des effets de pose, sous couvert d’un travail artistique pour montrer ces corps nus.

En toute logique, si l’on puis dire, qui Fleischmann a été parmi les premiers à photographier les nouveaux styles de danse à Vienne se voit proposer en 1925 de faire une exposition de ses photographies mettant en vedette la danseuse Claire Bauroff nue. Claire Bauroff dont le corps avait été très huilé, donnait ainsi aux cliché une luminosité et contrastes forts pris devant un noir. Quelques années auparavant, une telle mise en scène du corps nu aurait été impensable et en outre, la production de photos de nus pendant une longue période a été réservée aux hommes, en cela Trude Fleischmann était une pionnière, et à gagné ses galons ainsi. Cette exposition fît scandale et a fût interdite et les planches confisquées par un procureur de district de Berlin pour indécence.. une fois de plus , on note combien proposer du nu artistique est difficile et encore une fois, un des photographes dont nous parlons a été victime de censure

En raison de son origine juive Fleischmann a été obligé de chercher du travail ailleurs après 1938. Laissant derrière elle la plupart de ses négatifs, elle émigre à Paris, Londres et finalement à New York avec l’aide de son élève et ancienne amante Helen Post (1907-1979 une photographe indépendante qui a photographié les tribus indiennes dans tout l’Ouest et du Sud-Ouest de 1936 à 1941 ). [Fleischmann, qui ne s’est jamais mariée, était une lesbienne et a eu un certain nombre de relations avec des femmes connues].

Là bas, Fleischmann poursuit une brillante carrière dans la photographie, d’abord avec The Post et, après 1940, dans son propre studio, qu’elle a dirigé jusqu’en 1969 avec Frank Elmer, un autre émigré viennois.

Contrairement à son travail de jeunesse, beaucoup de ses photographies ultérieures sont des paysages urbains de New York, ainsi que des modèles de mode qu’ elle a souvent photographié pour Vogue. Ses clients, sont aussi les émigrants de la scène culturelle européenne, comme Elisabeth Berger, Oskar Kokoschka, Lotte Lehmann, Otto von Habsburg , le comte Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi et Arturo Toscanini.

En 1969, Fleischmann a pris sa retraite en Suisse, affirmant qu’elle ne voulait pas retourner à Vienne en raison du comportement de la population pendant la guerre. Après un accident en 1987 qui l’a rendue handicapée, elle est retournée aux États-Unis pour vivre avec son neveu, le pianiste Stefan Carell, à Brewster, New York jusqu’à sa mort en 1990.

Voir aussi les autres article sur Trude Fleischmann Ici

Trude Fleischmann – The dancer Tilly Losch ,1920-1930 Vintage silver print

Trude Fleischmann – Tilly Losch, 1925 gelatin silver print

Trude Fleischmann – Tilly Losch, 1925 gelatin silver print

Trude Fleischmann – Tilly Losch, nd

Trude Fleischmann –Tilly Losch-James 1932 Vintage silver print,

Trude Fleischmann -Tilly Losch im Spitzenkleid,1927

Trude Fleischmann -2 plate of Tilly Losch im Spitzenkleid,1927

Trude Fleischmann -Tilly Losch im Spitzenkleid,1927

Trude Fleischmann – Tilly Losch , around 1928

Trude Fleischmann -Tilly Losch im Spitzenkleid,1927

Trude Fleischmann – Tilly Losch , around 1928

Trude Fleischmann -Helene Thimig als Cordelia , 1929 – 1929 gelatin silver print

Trude Fleischmann –Helene Thimig 1927

Trude Fleischmann -The dancer Gertrud Falke from Leipzig , ca. 1927 ,Vintage silver print

Trude Fleischmann – The dancers Mila Cirul and Julian Algo. Vienna. Photograph around 1926

Trude Fleischmann Mila Cirul and Julian Algo, Photograph, Around 1926

Trude Fleischmann – Katta Sterna,(Reinhardt stages), Bromide gelatin silver print Issued by Eckstein Dresden – produced in approx 1924

Trude Fleischmann –Katta Sterna (dancer) 1925 Vintage silver print,

Trude Fleischmann Helene and Hermann Thimig in Goldoni play. Production by M. Reinhardt. 1924

Trude Fleischmann –Nude study Susi Birkmayer ~ 1930 Bromide silver, toned

Conseil de lecture Trude Fleischmann: Der selbstbewusste Blick by Anton Holzer & Frauke Kreutler , Catalogue Musée vienne, 2011 ou Catalogue: « Trude Fleischmann – Le regard confiant. » Edité par Anton Holzer et Frauke Kreutler. Editeur: Hatje Cantz, 2011

Né en Moravie, Franz Fiedler (1885- 1956) est l’élève du photographe allemand Hugo Erfurth. Ce passionné de photographie est considéré comme un excentrique durant son apprentissage alors qu’il travaille avec les plus grands d’Europe de 1905 à 1911 dont le photographe Rudolph Dührkoop. C’est en 1911 qu’il gagne le premier prix de photographie de l’exposition de Turin , il se fait un nom et expose à Prague en 1913. Il fait parti du cercle intellectuel de Jaroslav Hasek et Egon Erwin Kisch et installe son studio à Dresde en 1916. A Partir de 1919, il se lie d’une grande amitié avec Mme d’Ora (Dora Kallmus) et son mari , et il commence à travailler avec un appareil photo de pliage 9 × 12 , et en 1924 il est l’un des premiers photographes professionnels à utiliser un Leica.

Le studio de Fiedler a été détruit le 13 Février 1945 et tout ce qui restait était une boîte de photographies qui a été déposé avec sa famille en Moravie. Après 1945, il n’avait plus son propre studio et a gagné sa vie en RDA comme auteur de livres sur la photographie.

Others articles about Franz Fiedler (1885- 1956)

Elle dansait pieds nus, refusait le mariage, méprisait les conformismes, entendait vivre libre et “sans limites” selon sa devise. Véritable provocatrice, passionnée, audacieuse, bohème, Isadora Duncan a révolutionné la danse, bousculé les conventions de la danse classique académique dont elle rejetait les codes et les règles strictes en prônant une danse inspirée par la mythologie grecque et un retour à la symbiose du corps et de la nature. Vêtue de tuniques selon la mode de la Grèce Antique, Isadora a créé un style chorégraphique basé sur l’improvisation. “Une relation permanente, absolue et universelle, unit la forme au mouvement ; c’est là l’unique grand principe sur lequel je prétends m’appuyer car une même unité rythmique court à travers toutes les manifestations de la nature. L’eau, le vent, les plantes, les êtres vivants, les particules de la matière elle-même obéissent à ce ryhtme souverain dont la ligne principielle est l’ondoiement. la nature ne suggère nulle part des sauts ou des ruptures, il existe entre tous les états de la vie une continuité, un courant que le danseur doit respecter dans son art s’il ne veut pas devenir un pantin dénué de toute beauté. Chercher dans la nature les formes les plus belles et découvrir le mouvement qui exprime l’âme de ces formes, voilà la mission du danseur.” (1916, extrait du livre, La Danse de l’avenir, Isadora Duncan, éditions Complexe, 2003) Véritable prêtresse de la modernité, elle n’a jamais caché son attirance pour le communisme et la révolution russe en dansant sur l’Etude révolutionnaire de Chopin vêtue d’une tunique rouge. Elle a même tenté d’ouvrir une école populaire à Berlin, puis Paris et Moscou. Mais de sa vie entre les studios d’artistes de Londres, Paris, Berlin, en passant par la Grèce et des voyages en forme d’épopée antique et les grands palaces, ses amours difficiles et torturés avec l’acteur anglais Craig Gordon, le milliardaire paris Singer ou encore le poète Serge Essenine, on ne retient finalement de sa vie que sa fin tragique. Celle que l’on surnommait “Isadorable” est morte le 14 septembre 1927 dans une Bugatti, étranglée par son écharpe. “La liberté de la femme” “Si mon art devait être symbolique de quelque chose, ce serait de la liberté de la femme et de son émancipation vis-à-vis des préjugés qui sont la lice et la trame du puritanisme de la Nouvelle-Angleterre. Exposer son corps est un geste artistique, le dissimuler revient à commettre une vulgarité. Lorsque je danse, je ne fais pas appel aux instincts les plus bas de l’humanité comme le font, aux spectacles de variétés, vos filles à demi-nues. (…) La nudité est authentique, c’est de la beauté, c’est de l’art. C’est pourquoi elle ne peut jamais être ni vulgaire ni immorale. Si ce n’était pour avoir chaud, je ne porterais jamais de vêtements. Mon corps est le temple de mon art. (…) Le corps est beau, il est réel, il est vrai, il est libre. Il devrait susciter la vénération, non la répugnance car l’artiste est tout entier, corps et âme, dévoué à l’art. Quand je danse, je me sers de mon corps comme un musicien de son instrument, un peintre de sa palette et de ses pinceaux ou comme un poète des images issues de son imagination. Parce que je veux fondre mon image et mon corps en une seule et même image de beauté, je refuse de m’envelopper dans des vêtements gênants, de m’entraver les membres ou de couvrir la gorge. (…)”

Isadora Duncan 1922, {extrait du livre, La Danse de l’avenir, Isadora Duncan, éditions Complexe, 2003, pp. 104-105.}

Edward Steichen (1879-1973) -Isadora Duncan sous le portique du Parthénon à Athènes, 1920 Toulon, musée d’Art

Studio Apeda- Isadora Duncan’s pupils and adopted daughters, Irma, Anna and Erica Duncan, known as the Isadorables, 1916

Duncan was born in the United States but lived in Western Europe for the majority of her life, and essentially formed the basis of American Modern Dance. In a time when the traditional forms of dance and movement, particularly when it cam to ballet, were heavily indoctrinated, Duncan broke free by emphasising dance that was in touch and comfortable with the body and performed in unrestricted clothing and/or barefoot.

Duncan began dancing at a young age when her and her sisters taught dancing lessons to San-Franciscan children in order to bring in money for their mother who had divorced their father in 1880. When she was 22 she decided to move to London and then France and within two years she was beginning to make a name for herself. In 1909 she had enough money to open up her own dance school in a two story apartment which is also where she lived. Duncan’s theory for dance incoporated a much less institutionalised methodology as she focused on free and natural movements inspired by Ancient Greek Dance, folk dancing, nature and natural forces and incorporated an American emphasis on athleticism.

By 1924, after a brief stint in Moscow and a few years performing in and around Europe, Duncan opened up three new dancing schools: one in Grunewald (Germany), one in Paris and one in Moscow.

Duncan was very radical for a woman caught in the turn of the century. She was a fan of Communism, bisexual and had two children out of wedlock and to different men. Her daughter Dierdre (born September 24, 1906) and her son Patrick (May 1, 1910) both died in a car crash in 1913. Not long after it was rumoured that Duncan was in a relationship with Eleanor Duse (an Italian actress), something that has never been proven. In 1922 she married a Russian poet, Sergei Yesenin who was 18 years younger than her. His alcoholism brought her negative publicity and a year after they married he was institutionalised in a mental hospital, commiting suicide in 1925.

Duncan’s money troubles, alcoholism and scandalous love life are said to be the cause of her diminishing talent later in life as she moved from hotel to hotel across Paris and the Mediterranean, running up huge debts.

Duncan died on September 14, 1927. She was a passenger in a car driven by her rumoured lover, Benoît Falchetto a French/Italian mechanic. Duncan was always fond of long scarves and the one that was wrapped around her neck became caught in the spokes of the wheels causing her to be pulled out of the car on to the road with enough force so that she was probably killed instantly.

Sources : http://www.artnet.fr/magazine/expositions/deschodt/duncan.asp http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/

“When Lotte Jacobi’s photos were exhibited together for the first time four years ago, reviewers were dazzled by how many of Weimar Germany’s glittering jewels—from Käthe Kollowitz to Martin Buber to the famously vampy Lotte Lenya—had been captured by her lens. She seemed to have single-handedly taken on the task of portraying the immense artistic, psychological, and political fervor of those tumultuous years, which seemed fragile even at the time—an ambitious task for any one photographer, even one as hungry as Jacobi. But her atelier was, in fact, one of 400 in Berlin, and she was just one of the many—mainly Jewish—photographers feverishly recording the dancers, writers, and actors that made this doomed moment in German history so extraordinary. Another photographer who clicked away at an incredible rate and with singular results was Hans Robertson.

To say that an artist has been forgotten is to imply that he was well known in his time. Robertson’s name—like that of Jacobi and most other commercial photographers—was not familiar outside the circle of performers who were his subjects and magazine editors who used his services. But from the evidence of only a fraction of his prolific output, discovered almost by accident and now on display at the Berlinische Galerie in Berlin, his work deserves attention.

Robertson’s specialty was expressionist dance. And expressionist dance was huge in 1920s Germany: the avant-garde innovations that had taken place at the turn of the century in everything from painting to fiction became popularized, and dance was transformed from an aesthetic exercise into an attempt to translate the inner life into movement. The gestures of this modern dance were primitive, dramatic, almost ritualistic, with a fetishistic focus on the human body. Mary Wigman, one of its main innovators, slid across the floor on her knees, eyes closed, fists clenched, performing her Witch Dance. Her school in Dresden became a center of this Ausdruckstanz, producing world-renowned modern dancers like Harald Kreutzberg and Yvonne Georgi.

They all posed for Robertson. His studio on bustling Kurfürstendamm—a boulevard that was both the Fifth Avenue and the 42nd Street of Berlin—saw a steady stream of business in the late 1920s and early ’30s. But the commercial aspect of these photos, which were in demand by popular illustrated journals like the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung, is less important than the artistic vision that guided their creation. Robertson was trying to use his camera in much the same way the dancers he photographed were using their bodies. From the creative way he manipulated light to his innovative use of multiple exposures, he wanted to capture more than just straightforward ornamental shots of the dancers. He was trying to convey their new art form on its own terms.

This is clear in the photographs. The series called “Leaps,” of Gret Palucca, a favorite muse of expressionist painters and the Bauhaus crowd, catches Palucca in mid-air, limbs splayed. Only part of her body is in focus—the ability to photograph sudden movement was itself a recent technological advancement. In one image her naked torso is twisted, in another her back arched. Then there are the soulful photos of Jo Mihaly, performing her one-woman piece, “Mütter.” She stands in front of a black screen wearing a black turtleneck, her pale, emotive face almost floating in the frame and illuminated from above by a single beam of light. On the more abstract end are Robertson’s photos of Harald Kreutzberg performing his “Lunatic Figures.” Robertson overlays three different exposures of the famously shaved headed dancer, capturing the various expressions of madness Kreutzberg is embodying. Even in Robertson’s more straightforward photo of Kreutzberg as a lunatic, holding a flower and posed loose as a marionette puppet, he captures the dancer as a depersonalized body, a trope of Expressionism that would later inspire, among other post-war dance forms, Japanese Butoh.

Of Robertson’s biography, says the curator of the Berlinische Gallerie show, Thomas Friedrich, “there are more questions then answers.” He was born in Hamburg in 1883. After studying engineering—a profession that inspired a few early photos of construction sites and workers—he changed course and headed to St. Mortiz where he apprenticed for the Swiss landscape photographer Albert Steiner. At 28, Robertson’s first photo spread—a pictorial tour through Holland—appeared in Photographische Rundschau. But his photo career would have to wait until 1918, when he arrived in Berlin. There he joined Lili Baruch—one of the disproportionately high number of Jewish women then making her living with a Leica—who set up the studio on Kurfürstendamm, specializing in dance photography, which Robertson took over in 1928.

To produce the thousands of photos he printed over the next five years, Robertson most likely worked long days and weekends. In addition to dance photography, he shot a wide range of portraits of many of the era’s personalities, from the famous—a nude profile of the boxer Max Schmelling—to the forgottn, such as a close up of the publisher Irmgard Klepenheuer, gazing intently at the camera, a cigarette between her fingers.

In 1933, following Hitler’s appointment as chancellor and the subsequent boycott of Jewish businesses, Robertson had an inkling of what was to come. He handed over the studio to his apprentice, Siegfried Enkelmann. One of the few documents Friedrich, the curator, has been able to uncover is a contract signed by Robertson that makes the transfer final, and describes Enkelmann as “reliable.” And he was. The protégé survived the war and continued photographing dancers (including Mary Wigman) until his death in 1978.

Robertson and his coquettishly beautiful wife, the actress and dancer Inger Vera Kyserlinden (born Levin), escaped to her native Denmark. While the avant-garde movement had been taking place in Berlin, Paris, and Prague, most photographers in Copenhagen were stuck in the pictorial style of the 1910s. As a result, in 1963 Robertson established the first modern photography school in Denmark. But eight years later, just before Hitler began deporting Danish Jews, the Robertsons were forced into exile again, this time fleeing to Stockholm. They returned in May of 1945 and Robertson died just five years later at the age of 67. Thousands of his photographs were turned over to the Royal Library of Denmark following his wife’s death in 1969.

Over time, Robertson was reduced to little more than a footnote. And not just proverbially: It was literally in a footnote in 1992 that Friedrich—a charming, slightly disheveled curator who thrives on the detective work involved in resurrecting dead photos and their makers— discovered his name. He was intrigued, but it took another 14 years (after encountering Hans Robertson’s name in another context) for Friedrich to finally take a trip to Copenhagen to peruse the archive at the Royal Library. What he found there astounded him. Not only did Robertson’s photos offer the most comprehensive catalogue of Weimar dance, but his work was also that of an artist with a unique style and vision. Friedrich still marvels that Robertson’s photos manage to look so distinct from one another, even though they were all taken in the same studio.

The building that housed that studio, on Kurfürstendamm, no longer exists. Like it did in much of Berlin, new construction in the 1950s erased what was before. Now two pharmacies, a clothing store, and a nondescript café look out from the ground floor. There is no trace of the glamour and wild experimentation that was once captured there in pictures. But Hans Robertson himself might yet have an afterlife: Friedrich, it seems, is planning a large retrospective for 2011.” BY Deborah Kolben and Gal Beckerman [ freelance writers living in Berlin.]

Hans Robertson – Le Bain, 1933

Hans Robertson – Alfred Jackson Girls in Wintergarten, Berlin, 1922

Hans Robertson- Expressionist dance dancer unknown, Berlin,1920, (From documented the Weimer era dance scene in the 20′s)

Hans Robertson -The dancer Harald Kreutzberg in Irre Gestalten, Berlin, 1928

Hans Robertson- Unknown Dancer, Berlin, 1920′s

Hans Robertson -Little Viola, 1920′s

Hans Robertson -Zwaniger Jahre Atelier“Lili Baruch”, Berlin,1927

Hans Robertson The famous Weimar dancer Elizabeth Bergner, 1930

Hans Robertson- Lydia Wieser, nd ( probably 1920′s)

Hans Robertson- Gret Palucca, Berlin, 1930

Hans Robertson- Gret Palucca, 1920s

Helen Tamiris was a pioneer of American modern dance.

American choreographer, modern dancer, and teacher, one of the first to make use of jazz, African American spirituals, and social-protest themes in her work.

« Helen Tamiris (1903-1966), a founder of modern dance in the 1920s and 1930s, always kept a foot firmly planted in the commercial theater. She was trained in ballet at the Metropolitan Opera and by Michel Fokine, as well as in natural dancing at New York’s Isadora Duncan Studio. Her early career combined a soloist position in the Bracale Opera Company with appearances in nightclub and Broadway revues. Yet her first recital in 1927 demonstrated a personal expression of abstract movement and frank social analysis. A year later she adopted the Negro spiritual as a métier for life as conflict. Politically active, Tamiris helped to lead development of the Dance Repertory Theatre and dance initiatives under the Works Progress Administration Federal Art Project. She founded and chaired the American Dance Association and helped to set up the Federal Dance Project. Following World War II, she turned to Broadway to attract large audiences for a modern dance aesthetic that aspired to shape consciousness of the people. Tamiris choreographed eighteen musicals between 1943-1957, artfully integrating dance into such productions as Up in Central Park, Annie Get Your Gun, and Fanny. She taught movement to dancers and actors and formed the Tamiris-Nagrin Dance Workshop in 1957 with Daniel Nagrin, who was her husband at the time. » Helen Tamiris, an essay by Elizabeth McPherson.

Soichi Sunami– The dancer Helen Tamiris , 1930’s {from the Dance Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations}

Edwin Curtis Moffat (11 Octobre 1887 – 1949), mieux connu sous le nom Curtis Moffat, était un photographe , mais aussi un peintre et architecte d’intérieur moderne. originaire de New York. Moffat a étudié la peinture à New York et à Paris avant d’exposer son travail à New York pendant la Première Guerre mondiale.Il a épousé l’actrice et poète Iris Arbre, et le couple s’installe à Londres après la guerre.

Parmi les nombreuses influences artistiques surréalistes, a eu une relation très étroite avec Man Ray, avec qui il a collaboré à Paris échanger des idées, des styles et des installations. Outre sa collaboration avec Man Ray, il fût également très proche de Cecil Beaton avec qui il a travaillé à de nombreuses reprises tout au long de sa carrière.

Il a ouvert un studio de photographie à Londres en 1925( date à laquelle a été publié dans une édition de 20 exemplaires par Factum Art des célèbres portraits de Nancy Cunard, écrivaine) .

Quatre ans plus tard, il a ouvert une salle d’exposition de design d’intérieur et une galerie, affichant un mélange de mobilier moderne tribales, antique et africains. Sa maison est devenue un salon populaire pour les artistes, les intellectuels et les gourmands.

Il est revenu à l’Amérique en 1939 avec sa seconde épouse, de s’installer sur Vignoble Martha, où il a continué à peindre.

Curtis Moffat – Mrs Hamilton, 1925-1930

Curtis Moffat – Mrs Hamilton, 1925-1930

Curtis Moffat-‘Lady Diana Cooper’ (Viscountess Norwich), About 1925

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat- ‘Lady Diana Cooper’ (Viscountess Norwich), About 1925

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat, ‘Nancy Cunard’, About 1925

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat -Nancy Cunard (1898-1965), writer, diptych, London, UK, c.1925. © Curtis Moffat Victoria and Albert Museum

Curtis Moffat, ‘Tallulah Bankhead’, About 1925

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat, ‘Daphne Du Maurier’, About 1925

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat, ‘Daphne Du Maurier’, About 1925

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat -Lady Diana Cooper devant un portrait de man Ray et dans l’atelier de Motaff, où l’on aperçoit le portrait d’Isis sa femme, 1925

Curtis Moffat, Portrait of a woman, About 1925 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat, ‘Tallulah Bankhead’, About 1925 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat-‘Cecil Beaton’, About 1925

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat, ‘Still life’,About 1925-1930

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat- a pair of acrobatic dancers of the Jazz Age,’Hoffman and Greville’,About 1925

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat- Ms Greville Gelatin silver print. London, UK, c.1925. © Curtis Moffat Victoria and Albert Museum

Curtis Moffat- Ms Greville Gelatin silver print. London, UK, c.1925. © Curtis Moffat Victoria and Albert Museum

Curtis Moffat- Ms Greville Gelatin silver print. London, UK, c.1925. © Curtis Moffat Victoria and Albert Museum

De nombreuses études de nus de Moffat comprennent une série de modèles féminins posant avec des masques africains. Bien qu’elles aient étées inspirées par les célèbres photographies « Noir et Blanche de Man Ray » (1926), l’intérêt pour l’Afrique et ses sculpture était aussi la dernière tendance avant-garde de cette période.

Curtis Moffat, ‘Nudes with African masks’, About 1930

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat, ‘Nudes with African masks’, About 1930 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London /Estate of Curtis Moffat

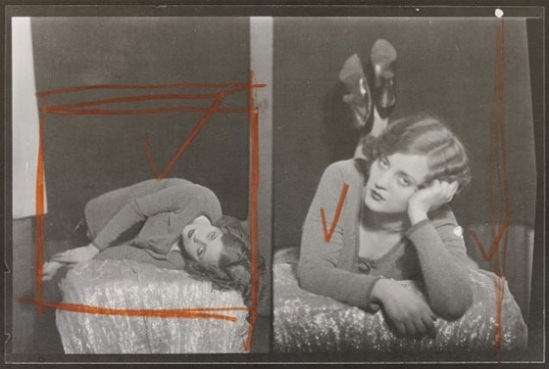

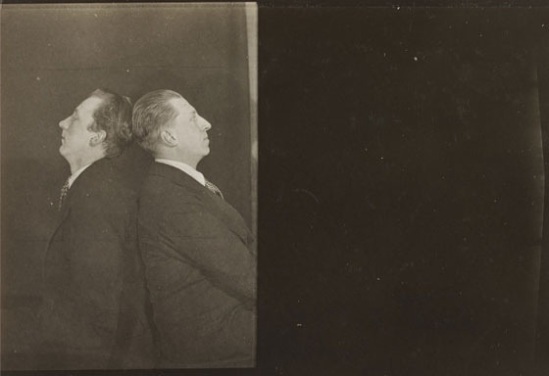

Curtis Moffat, ‘Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell’, (the literary brothers Sitwell as a pair of doubles, seated back-to-back.), About 1925

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

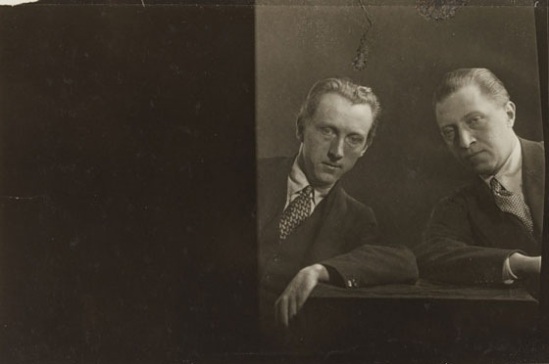

Curtis Moffat- ‘Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell’ ( the literary brothers Sitwell as a pair of doubles, seated side-by-side) .About 1925

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

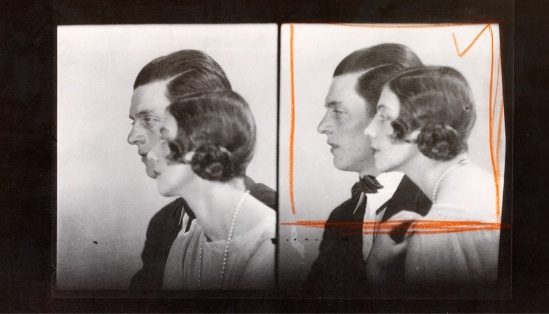

Curtis Moffat, ‘Unidentified couple’, about 1925.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Curtis Moffat- Portrait of a man, Gelatin silver print. London, UK, c.1925. © Curtis Moffat Victoria and Albert Museum

Curtis Moffat, ‘Portrait in mirror’, about 1930.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

Moffat a fait sans appareil photo ces photogrammes en plaçant des objets directement sur papier photographique, qu’il a ensuite brièvement exposé à la lumière. Il a appris la technique de Many Ray, qu’il appelait les Rayographes de « ses photogrammes » ils ont étés publiés par par Factum Art.

Curtis Moffat, ‘Abstract Composition’, About 1925

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Estate of Curtis Moffat

To make this striking image of a dragonfly, Moffat placed the specimen in the photographic enlarger head (in place of a negative) and projected the image onto photographic paper

Mareille Baum by Hans Natge, Berlin around 1915

Mareille Baum by Hans Natge, Berlin around 1915

Mareille Baum by Hans Natge, Berlin around 1915

Laure Albin Guillot –Portrait présume de La princesse Maria Klavdievna Tenicheva (княгина Мария Клавдевна Тенишева), 1908-10

Benedykt Jerzy Dorys est principalement connu en tant que très grand portraitiste (photographique). Son studio, basé à Varsovie, déjà avant la guerre, était un lieu des plus tendance pour ne pas dire « branché » de la Ville de Varsovie et et se faire photographier Dorys n’était pas seulement de bon goût, mais révélait un signe d’appartenance à crème de la crème de l’époque.

Moins connues, mais tout aussi intéressantes sont ses photos de mode et ses quelques photos artistiques du corps nus. Dorys adorait les femmes et a su en sublimer toute les beauté et ce que je vous propose aujourd’hui à travers des portraits et des nus

Jerzy Dorys Benedykt- Act II, 1932

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.