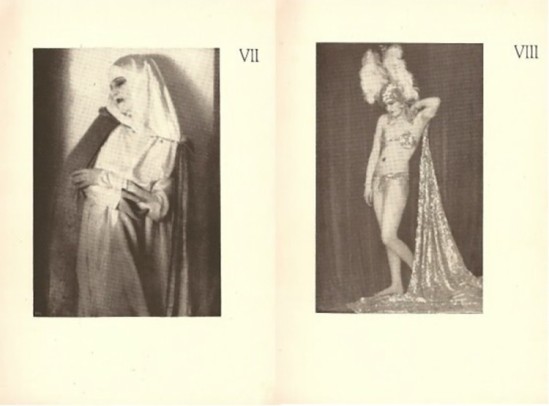

Présenté ici les scans du livre, Madame d’ora – photography for Dances of Vice, Horror, & Ecstasy written and danced, by Anita Berber & Sebastian Droste, 1923. les photographies ont été prises en 1922. j’y ai ajouté des tirages plus clairs de ce livre.

Anita Berber (1899-1928), and to a lesser extent her husband/dance partner Sebastian Droste (1892-1927), have come to epitomise the decadence within Weimar era Berlin, their colourful personal lives overshadowing to a large extent their careers in dance, film and literature. Yet the couple’s daring and provocative performances are being re-assessed within the history of the development of expressive dance, and their extraordinary book ‘Tänze des Lasters, des Grauens und der Ekstase’ (‘Dances of Vice, Horror and Ecstasy’-1922), is a ‘gesamkunstwerk’ (total work of art) of Expressionist ideology largely unrecognised outside a devoted cult following.

Berber is the better known of the couple. Born in Dresden into a liberal middle class family, her parents separated a year later. Her father remarried and her mother, in pursuit of acting career, left Anita in the care of her grandmother. Berber was partly educated in the newly built Jaques-Dalcroze institute at Hellerau, a progressive utopian experiment which extolled the principles of natural harmony in work and everyday life, and used euthythmics as a teaching method. Eurhythmics aimed « to enable pupils, at the end of their course, to say, not « I know, » but « I have experienced,” « (Emile Jaques-Dalcroze, ‘Rhythm Music & Education’). Mary Wegman (1886-1973), who would develop ‘ausdruckstanz’ (expressive or Expressionist dance) and later become one of the century’s major choreographers, was also a pupil at the same time as Berber, though it is not known if they ever met. Below is a 1921(?) clip of Wigman performing ‘Hexentanz’.

At fourteen Berber rejoined her mother and, moving to Berlin, joining a troupe of performers led by Rita Sachetto initially performing alongside another influential dancer Valeska Gert (1892-1978), much of whose work is now regarded as proto performance-art. Berbers style, formally influenced by Eurythmics, began to incorporate Expressionist sensibilities and this mixture – fused with her dynamism and intense sexuality, gained her press notices which soon led her to be hailed as a new ‘wonder in the art of dance’.

She also began to develop a film career performing in a number of films directed by Richard Oswald (1880-1963). These included the melodrama, ‘Prostitution’ (acting alongside Conrad Veidt) and the equally controversial ‘Different From The Others’ (both made in 1919) the later taking homosexuality as its theme. Berber also appeared briefly in Fritz Langs’ ‘Dr Mabuse’ (1921).

Her personal life also contributed to raising her public profile. Married, in name only, to an Oswald scriptwriter, she conducted numerous lesbian alliances (Marlene Dietrich allegedly among them) and fuelled her polysexual/decadent lifestyle with vast ingestions of cocaine, cognac, opiates and ether.

*********

Sebastian Drostes background is more obscure. He was born Willy Knobloch into a wealthy manufacturing family in Hamburg where he went to art school emerging as « a classic dandy, acerbic homosexual and art snob » (Mel Gordon: ‘The Seven Addictions and Five Professions of Anita Berber: Weimar Berlin’s Priestess of Decadence’ p. 116).

He was drafted in 1915 and disappears from view, to resurface in 1919 in the major Epressionist journal of the day ‘Die Sturm’ to which he contributed poetry. Later that year he moved to Berlin and as ‘Sebastian Droste’ began work as a dancer for the Celly de Rheidt company which specialised in what were termed ‘schönheitsabende’ (beauty evenings), the ‘beauty’ aspect being the near nakedness of the performers. They specialised in performing ‘artistic’ interpretations of ‘uplifting’ classical works which they hoped would prevent them from attracting police attention. However De Rheidts’ luck expired in 1921 with their interpretation of Philip Calderons’ painting, ‘St. Elizabeth of Hungary’s Great Act of Renunciation’ (1891) probably for its’ blasphemous content rather than obscenity (though the subsequent discovery that some of the performers were underage did not help). As a result of this Droste became unemployed.

With Berber now a film starlet, dancer of note, and already fictionalised in a novel by Vicki Baum entitled ‘Die Tänze der Ina Raffay’ Droste was able to obtain a contract for them to perform material at Viennas Great Konzerthaus-saal. This production was to become the ‘Dances of Vice, Horror and Ecstasy‘. Created in just under five months it was a mixture of old Berber material and new works to be danced by Berber and Droste either together or as solo pieces. The book of the same title was also produced, though this was not published until the following year.

The show received mixed reviews, but was overtaken by scandal when Droste was arrested for attempting to pass a forged credit note for 50 million Kroner in order to partially pay off his own and Berbers’ debts. Drostes’ creditors convinced the court to allow him to continue working until it went to trial. If they could continue to perform, they would make money to pay their debts. However, Droste then signed ‘exclusive’ contracts with three different theatres and although one theatre eventually managed to gain exclusivity, the couple also broke that agreement. The International Actors Union became involved and banned them from performing on any continental variety stage for two years.This was the beginning of the end of their relationship. The publicity generated made them notorious in Germany and Austria, but they had little opportunity to work and drug habits to maintain. Both returned to Berlin. In October 1923 Droste stole what he could of Berbers jewels and furs using the money raised by their sale to leave for New York. They had been married for ten months. Berber had rapidly divorced Droste and managed to pull herself together enough to form ‘Troupe Anita Berber’ performing in various Berlin night-clubs, though once again her volatility resulted in bans and dismissals. She quickly married American dancer Henri-Chátin Hoffman in autumn 1924. He helped to revive Berbers career with shows featuring a mix of old favourites such as ‘Morphine’ (its music, specially composed for her by Mischa Spoliansky was a hit of its day) and new material.

*********

The book

Berber and Droste chose to express themselves almost exclusively through the Expressionist/Modernist ethos, which was in itself filtered through the angst of Germany during the Weimar period.

Expressionism had been in existence before Weimar and, like many art movements, it had no formal beginnings, as opposed to a ‘school’ of artists who might band together under a common technique. It was fundamentally a reaction against the Impressionists who were seen by the Modernists as merely portrayers of ‘reality’ but who had failed to add anything of the artists own interior processes such as intuition, imagination and dream. This new wave of artists found inspiration in painters such as Van Gogh and Matisse but also drew from writers such as Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and the Symbolists, together with the philosophy of Nietzsche and Freudian psychology.

Expressionists believed the artist should utilise « what he perceives with his innermost senses, it is the expression of his being; all that is transitory for him is only a symbolic image; his own life is his most important consideration. What the outside world imprints on him, he expresses within himself. He conveys his visions, his inner landscape and is conveyed by them ». Herwert Walden: ‘Erster Deutscher Herbstsalaon’ (1913).

The image is the poem as portrayed in the book by D’Ora. Interestingly, it is doubted whether the dance was performed (at least in Vienna) topless. Once again, this would indicate that the book is to be considered as its own specific entity.

The poems cite their inspirations: artists Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso and Matthias Grünewald and authors lsuch as Villiers De L’Isle Adam, Edgar Allan Poe, Paul Verlaine, E.T.A. Hoffman and Hanns Heinz Ewers

One Poem from the book

Cocaïne / Danced by Anita Beber/ Music By saint Saëns

**********

Madame d’ora – photography for Dances of Vice, Horror, & Ecstasy written and danced, by Anita Berber & Sebastian Droste, 1923

Madame d’ora – photography for Dances of Vice, Horror, & Ecstasy written and danced, by Anita Berber & Sebastian Droste, 1923

Madame d’ora – photography for Dances of Vice, Horror, & Ecstasy written and danced, by Anita Berber & Sebastian Droste, 1923

Madame d’ora – photography for Dances of Vice, Horror, & Ecstasy written and danced, by Anita Berber & Sebastian Droste, 1923

Madame d’ora – photography for Dances of Vice, Horror, & Ecstasy written and danced, by Anita Berber & Sebastian Droste, 1923

Madame d’ora – photography for Dances of Vice, Horror, & Ecstasy written and danced, by Anita Berber & Sebastian Droste, 1923

Madame d’ora – photography for Dances of Vice, Horror, & Ecstasy written and danced, by Anita Berber & Sebastian Droste, 1923

Madame d’ora – photography for Dances of Vice, Horror, & Ecstasy written and danced, by Anita Berber & Sebastian Droste, 1923

Madame d’ora – photography for Dances of Vice, Horror, & Ecstasy written and danced, by Anita Berber & Sebastian Droste, 1923

Madame d’ora – photography for Dances of Vice, Horror, & Ecstasy written and danced, by Anita Berber & Sebastian Droste, 1923

Vous devez être connecté pour poster un commentaire.